Overview

Consensus is an "agreement" problem.

- Consensus

- A collection of processes "agree" on a value after one or more processes propose values

Qualities

- Safety: all agree on some value eventually

- Liveness: all agree on the same value

Applications

- Two Generals Problem: attack or retreat?

- Financial transaction between two entities

- Data copy across multiple storage nodes

- Mutual exclusion

- Leader election

- Totally-ordered multicast

The Problem of Consensus

Problem Definition

- A collection of processes \(p_i, i \in \mathbb{N}\)

- Processes can fail, but message delivery is reliable

- Each process \(p_i\) proposes some value \(v_i\)

- each process has a decision variable \(d_i\)

Each process has two states: \(\{decided, undecided\}\)

Goal

- set values to \(d_i\)

- agree on \(d_i\) value - everyone shares the same \(d_i\).

Solution

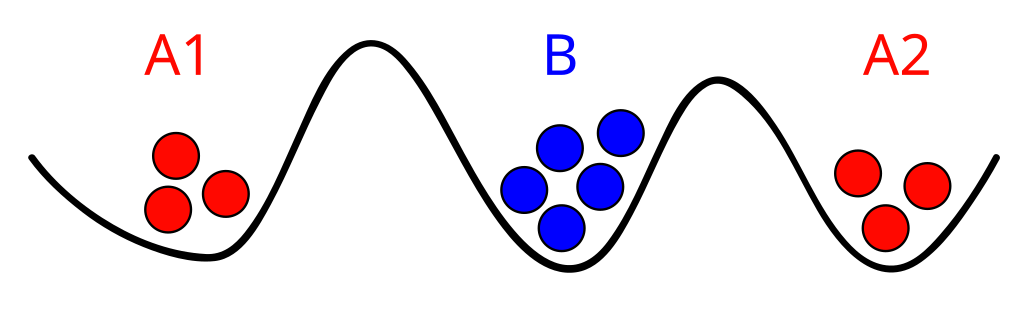

Things become arbitrarily complicated when we introduce the possibility of process failure.

In most cases, proposed values are binary, with processes picking the majority value.

Consensus Requirements

Consensus in the presence of failures requires a notion of failed processes and correct processes.

Requirements

- Termination (liveness)

- Agreement (safety)\[p_i, p_j \text{ correct} \implies (d_i = d_j)\]

- Integrity (safety)

Integrity can be of a weaker type - not all processes necessarily need to agree

Consensus Algorithm

First, let's think about how to design an algorithm under the assumption that no process fails.

- All processes \(\{p_1, \dots, p_n\}\) collect all values \(\{v_1, \dots, v_n\}\) other processes propose.

- Each process \(p_i\) computes \(d_i\) as \[d_i = \text{max}(\{v_1, \dots, v_n\} \cup\text{undecided})\]

Analysis

Does this algorithm terminate?

- Yes (if no process failures and message delivery is reliable)

- If processes might fail:

- in synchronous model, the algorithm can be modified to terminate

- in asynchronous model, you cannot guarantee termination

Does this algorithm guarantee agreement?

Does this algorithm guarantee integrity?

Majority function (or some other - min, max, etc.) ensures agreement and integrity are upheld.

Consensus in Synchronous Model

Process can detect reliably if another process has failed, dropping the process from the consensus.

The algorithm runs in rounds. Consider a situation in which \(f\) failures are acceptable:

- at each round, all correct processes collect proposed values from all others

- repeats the process \(f + 1\) rounds

After \(f + 1\) rounds, correct processes will agree.

Algorithm for process \(p_i \in g\); algorithm proceeds in \(f + 1\) rounds.

On initialization:

- \(values_i^1 := \{v_i\}, values_i^0 := \emptyset\)

In round \(r\), \(1 \leq r \leq f + 1\)

- in round $r$:

- on $B-deliver(V_j)$ from some $p_j$

- $values_i^{r+1}$

- on $B-deliver(V_j)$ from some $p_j$

There are at most $f$ failures, and the algorithm runs for $f + 1$ rounds. We show that all processes get the same final set of values.

Assume processes $P$ and $Q$ differ in one value $v$.

Variants of Consensus

- Consensus

- each process proposes a value

- all correct processes agree on a single value

- Interactive Consistency (IC)

- Each process proposes a value

- All correct processes agree on a vector of values, not a single value

- Byzantine General Problem (BGP)

- One special process proposes a value

- All other correct processes agree on that value

- Process can be malicious or faulty

Byzantine General Problem (BGP)

Consider cases when processes may fail arbitrarily (not crash-stop)

Commanders as well as lieutenants can be treacherous (faulty).

- command tells one lieutenant to "retreat" and another to "attack"

- one lieutenant tells one peer that the commander said to "attack" but tells another peer he said to "retreat"

BGP in Synchronous Systems

Unlike consensus, processes can be faulty

- message proposes any arbitrary value

- can change values inside messages when they pass values to others

- may remain silent/omit messages to send

- correct processes can detect absence of message, but can't conclude failure (because it may remain silent and come back)

Only one process (the commander) supplies a value that the other processes are to agree upon instead of each of them proposing a value.

Requirements

- Termination

- Agreement: the decision value of all correct process is the same: $p_i = p_j \implies

- Integrity: if commander is correct, then all correct processes decide on the value the commander proposed

It can be formally shown that with 3 processes where one can be faulty, it is impossible to design an algorithm that can solve BGP.

- This isn't true if generals can sign their messages.

Impossibility with $N \leq 3f$

Assume a solution exists with $N \leq 3f$.- Let each of three processes $p_1, p_2, p_3$ use this solution to simulate the behavior of $n_1, n_2, n_3$ generals respectively.

- where $n_1 + n_2 + n_3 = N$ and $n_1, n_2, n_3 \leq \frac{N}{3}$.

- Assume that one of the three processes is faulty.

- Those correct processes will simulate correct generals.

- The faulty process's simulated generals are faulty

- the messages that it sends as part of the simulation to the other two processes may be spurious.

- Since $N \leq 3f$ and $n_1, n_2, n_3 \leq \frac{N}{3}$, at most $f$ simulated generals are faulty.

Possible if $N \geq 3f + 1$.

- $N = $ number of processes

- $f = $ number of faulty processes.

BGP

Impossibility of Consensus

Fisher et al. proved that no algorithm can guarantee to reach consensus in an asynchronous system, even with one crash failure.

Partial Synchrony

-

"No guarantee" doesn't mean process never reach consensus with one faulty process

- impossibility in the limit

- consensus is fairly regular!

-

To work around impossibility, we consider partially synchronous systems

- sufficiently weaker than synchronous systems

- sufficiently stronger than asynchronous systems

Achieving Partial Synchrony

- Masking faults

- Consensus with failure detectors

- Consensus with randomization